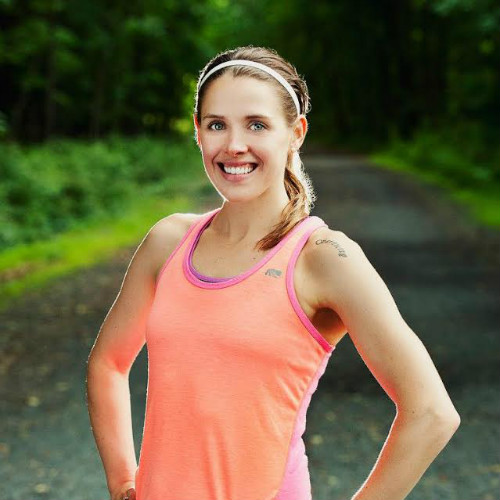

I don’t do things halfway (read: I often take things to the extreme). So, if you’d have told me even three years ago that I would be shopping for a bikini to wear in San Diego this summer, I’d have laughed in your face. Impossible.

See, I believed perfection was possible. When it came to eating, fewer calories were always a little more perfect. When it came to exercise, more was always better. And when it came to physical appearance? Nothing represented my desire for perfection more than my desire for the elusive six-pack abs.